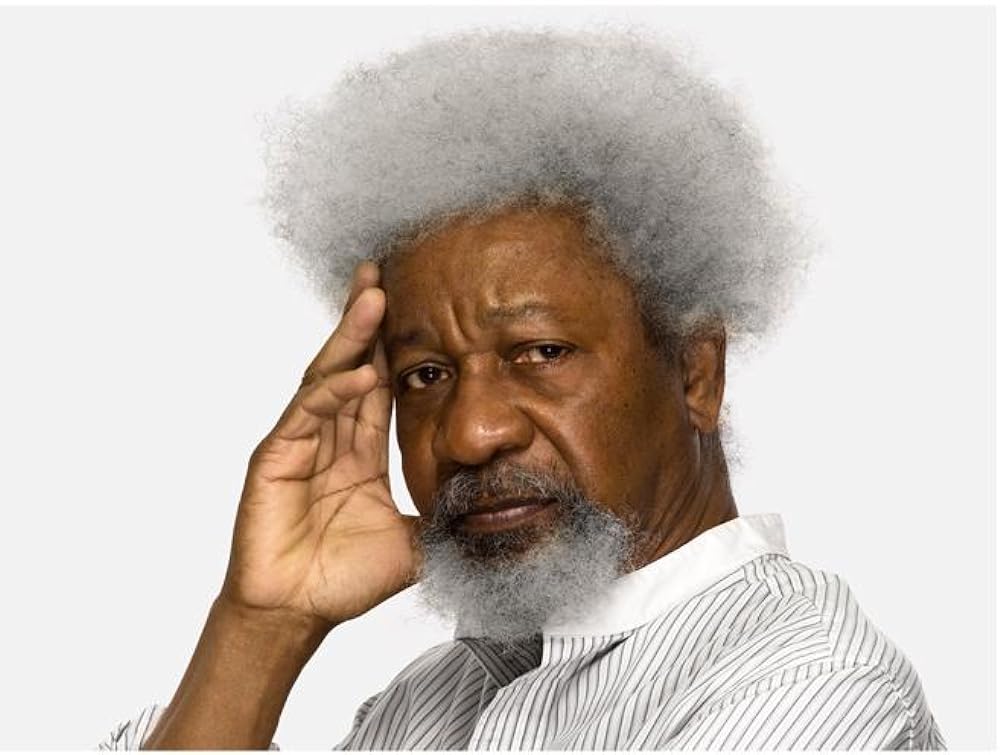

A torrent of tributes poured in from different parts of the world as Black Africa’s first Nobel Laureate, Professor Wole Soyinka clocked 90 years penultimate weekend. Whether in speech or in writing, Soyinka’s attainments both as a writer and activist had received the most profound, commendatory appraisal from a broad spectrum of scholars, the intelligentsia, literati, the academic community, and the larger society.

I have decided to reproduce a piece titled “The Genius in Wole Soyinka” I did way back in July 2004, when this exceptionally great man attained 70 years. Excerpts:

The greatness of the life of Wole Soyinka whose corpus of literary works spans all the genres of literature is the reason for the festival of this season. It’s understandable why many people, including this writer who has followed the course of Soyinka’s literary career also joined in the mirth of the moment. We are celebrating literary creativity of an individual with a remarkable impact in an increasingly meaningless world, and not the accrual of billions of naira to individuals from less transparent sources much of which is insulated from innovative or identifiable entrepreneurial exertions.

I cannot explain my appreciation of the peculiar course of Soyinka’s literary works without letting people into my gradual development in the rigorous nature of literary scholarship. Personally, I have experienced two-phased understanding in relation to the rigours of appreciating acclaimed literary works. As it was in those early years of my initiation into literature, first as a secondary school student in my ancestral home, Amai, and later in my Higher School Certificate (HSC) days at Government College, Ughelli, I only managed to glean the works of Soyinka and his contemporaries from a literal perspective. The quest spirit in me then was merely latent; so I could not do much other than accept the interpretations by my teachers whose approach I have seen in latter years of enhanced literary consciousness as overly simplistic, trite, warped, and denotative.

Each time I try to recollect those introductory classes in literature where such an all-important poem “Abiku” was taught on a plain level of appreciation, I just laugh at what were obvious literary infirmities of my former teachers. Perhaps, they were afflicted with thought dysfunction caused by literary shallowness, or that the hidden thoughts of Soyinka’s thematic preoccupations confounded their knowledge!

But how time flies in every aspect of life! It was not until my days in the university, especially after I had chosen literature emphasis towards the end of a three-year course in English & Literary Studies that some light in my own understanding began to illuminate the shadowy frontiers of Soyinka’s works. During that period, I quickly discovered that the tenor of Soyinka’s avant-gardist viewpoint is quite pervading, and as complex as the bible, it yields a new layer of meanings each time an individual undertakes a studious exploration of his works.

The greatness of Soyinka, our icon and Nigeria’s gift to the world, springs from his creative endeavours spanning all the genres of literature, namely prose fiction, drama, and poetry, and the adjuncts such as essays, autobiography, memoirs et cetera. Anyone conversant with literary scholarship is aware that it takes only a genius to be credited with excellence in a particular genre, much less becoming accomplished in the three genres.

Although, he is most known for drama, which ascribes the appellation of Black Africa’s Foremost Dramatist to his luminous status, Soyinka authored two novels The Interpreters and A Season of Anomie besides various collections of poems. Given the canon of over 17 plays in his authorial possession, his place in the corpus of world literature was already assured even if he had not put his creative energy to use in either prose or poetry. There lies the strength of a man with an exceptional depth of creativity that his voice and towering figure on the African continent and beyond cannot be disputed. He possesses a rare fecundity of mind that the celebrated novelists such as Chinua Achebe, Ayi Kwei Armah, and Ngugi wa Thiong’o lack in poetry and drama.

Beyond the shores of Nigeria, not all the great writers in the class of Nobel laureates excelled in more than a genre. George Benard Shaw, the second greatest English dramatist after William Shakespeare, restricted his creativity to drama like the latter whose time did not witness the birth of prose fiction until the advent of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe in 1719, almost a century after Shakespeare’s demise. Besides the volumes of poetry for which their geniuses earned acclamation, neither W.B. Yeats nor T.S. Eliot wrote any form of novel. Recipients of the Nobel awards after Soyinka such as Derek Walcott, Toni Morrison and Nadine Gordimer are reputed for using appropriate themes to advance the cause of humanity.

The complexity of Soyinka’s writing derives mostly from his uncanny rebellion against established dramaturgy in conception and presentation. His skill in the fusion of the mythic Ogun and its metaphors derived from Yoruba and, by extension, African belief system, is the single most important aspect of his dramatic essence. This was validated by the Swedish Academy, which in its citation for Soyinka’s Nobel prize in 1986, said he was a writer, “who, in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones, fashions the drama of existence.”

At the incipient stage of his career, numerous literary critics in the Euro-American axis were not keen on giving him a chance as he forged a relatively new style other than the predominant mode in the West. In literature, one could hardly be great without forging a new idiom with which a writer could express his perception of the world, including the physical realm and another beyond human comprehension as well as the unfathomable predilection of man for bestiality.

Soyinka’s denunciation of previous forms is discernible in a conscious attempt to communicate his individual and the African experience to a larger world audience. We have found such phenomena in the past as every literary age tends to dump the taste of the preceding era. For instance, the English Romantic age had William Wordsworth, S.T. Coleridge, Lord Byron, P.B. Shelly, John Keats among others that denounced the canons of the Neoclassical Age. The same strand is perceptible in the distinctive style of the modernist era in obvious contradistinction to the flavour of Victorian age under which the Poet Laureate Alfred Lord Tennyson blossomed in England.

In African literature, there has been a shift from the noticeable themes of cultural conflict in the pre-independence era to the disillusionment emanating from poor leadership by the successors of the colonialists on one hand and the neocolonial dominance of African countries by Western powers on the other hand. That an interrogation of the beneficial import of independence to the African countries has birthed some form of protest literature is not surprising.

In every material classification, the political activism of Soyinka in the blighted course of Nigeria has provided much lustre to his image. In true conformity to commitment in writing, Soyinka’s contribution to the cause of social justice and an envisioned egalitarian society could only pass unnoticed in the minds of persons that do not share his viewpoint. His role in this particular area as well as his creative excellence has helped to imbue us with the benefits of an enduring faith in the pursuit of scholarship. It also enhances the visible appreciation of heroism in its strict sense, particularly in the light of our current national experience in which a distortion of the concept seemed to have been legitimised in some way.

Many discerning Nigerians are witnesses to the acclaimed glory and reputation brought by Soyinka to Nigeria. We are becoming more aware that the greatness of a man is neither determined by the number of property he has acquired in various elitist districts of any geopolitical entity, nor his number of factories, nor immeasurable wealth that an opportunist masquerading as a politician could garner in a corrupt country like Nigeria.

The immortal tone of a man’s life after his sojourn must reflect how much his achievements could extricate mankind from the web in which we have been enmeshed, either arising from the unforeseen hands of ill fate or the endless tragic contrivances of man. Look at the lives of Nelson Mandela, Julius Nyerere, Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah, Marcus Garvey, Martin Luther King, Jr. among others. Then look at Soyinka. What do you find? It is greatness at its greatness. It is on account of this that most of our people idolise Soyinka, who, despite being a mere mortal, would be remembered possibly like Shakespeare for whom Ben Johnson, the foremost comedian in English literature, described in a commendatory poem in 1623 that “He was not of an age but for all time.”

*Tony Eke, journalist and literatus, lives in Asaba, Delta State capital.